When I first saw Dhruv in that TT club room, I never anticipated he could be a district level champion in TT while playing with his left hand because his right hand was amputated with an artificial limb from the elbow joint.

He couldn’t be, could he?

Has God endowed him with the ability to play table tennis with just one hand?

On his last seat bus ride to a college function, he lost his right hand in an accident, and his right elbow was hit by a speeding truck from behind.

Of course, it’s pitiful.

We made friends during our evening TT session, and when I asked him about his perception of the imputed right lmb, he grinned and stated, “How could any touch cause a sensation in my arm?”

That’s what our sense of touch is all about!

You can close your eyes and picture what it’s like to be blind, or you can close your ears and imagine being deaf.

Touch, on the other hand, is so important and pervasive in our lives that we can’t picture life without it.”

Though David Linden, a Johns Hopkins neurobiologist, correctly said in his book Touch: The Science of Hand, Heart, and Mind, my district-level TT champion friend Dhruv can feel it on a dipper level.

Touch is one of the most underappreciated senses.

Every second of the day, we acquire tactile information about the environment around us.

If you’re seated right now, your butt is crushed into your chair.

Your fingertips are most likely contacting or swiping your smartphone’s LED screen.

All of this data is so pervasive that the only way to make sense of it is to shut out the majority of it — you probably weren’t paying attention to these sensations until you read what touch means to those who have lost body parts or are partially paralysed.

Do you realise that you have a unique system for sensing emotional and social touch?

Linden explains, “There are two touch systems.”

“We call discriminative touch one that delivers the ‘facts’ — the location, movement, and power of a touch.”

“But there’s also the emotional touch system to consider.

It uses unique sensors called C tactile fibres to transmit information at a considerably slower rate.

It’s a little hazy about where the contact is happening, but it transmits data to the posterior insula, a portion of the brain that’s important for socially bonding touch.

This involves everything from a friendly hug to your mother’s touch when you were a youngster to sexual touch.”

As you may be aware, the sense of touch is essential for everyday tasks: people who lack it may struggle to crack an egg, raise a cup, or even turn a doorknob.

But what about Dhruv, my table tennis partner, who lost his right hand?

With his artificial right limb, can he sense the human touch on his arm?

When I questioned him if he can detect his feeling on his amputated right limb while playing with just his left hand, He simply grinned, his eyes filled with a thousand questions.

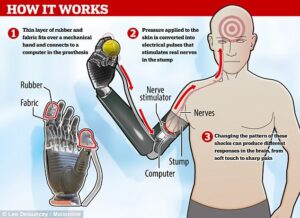

Because I am so good at table tennis with my left hand, I believe that recovering this sensibility is a primary priority for artificial limb designers, which Bensmaia, a new breed of neuroscientist, is fully aware of, as he stated in Science News.

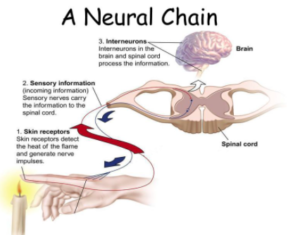

When you touch anything, your brain registers it.

The brain receives messages from the hand indicating that contact has been made.

However, according to a new study conducted on monkeys, the sensation of touch may not require real contact.

The animal will believe its finger has touched anything if brain cells are zapped.

My friend Dhruv, who has lost a limb, would undoubtedly require a prosthetic limb to do daily duties.

Is he, however, actually aware of the objects he holds?

The latest discoveries point to the possibility of giving patients who use mechanical limbs a sense of touch in the future.

The new tests were developed by University of Chicago psychologist Sliman Bensmaia. The findings of his group were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on October 14.

At least in mice, a team of researchers from the ISIC’s Institute of Neurosciences in Alicante discovered that the sense of touch develops in the brain before birth. The group describes their research into the embryonic phases of brain development in mice, as well as what they gained from it, in a report published in the journal Science.

Scientists have been studying the formation of a sense of touch for many years, but it is still unknown how it develops.

Prior study has demonstrated that once it develops, it leaves an imprint on the cerebral cortex in the form of a map.

Some researchers believe that before birth, a fundamental map is established in the brain, and data points are added as neonates develop—sensory input from various body parts is simply added to the map.

However, research from a team in Spain reveals that the map is already in place by the time a kid is born, so that viewpoint may have to shift.

When it comes to people who have had sections of their bodies amputated or who suffer from neurological illnesses, the limitations of earlier explanations for how and where our brain functions interact become obvious.

Professor Dr Tobias Heed, one of the study’s authors, says

His research group “Biopsychology and Cognitive Neuroscience” is a collaboration between CITEC and Bielefeld University’s Department of Psychology.

“People who have had a hand or a leg amputated frequently experience phantom sensations in their limbs.”

But whence does this erroneous view originate?

To begin answering this question, Heed investigated if phantom experiences may be discovered in healthy people, in collaboration with Dr Stephanie Badde (New York University, USA) and Professor Dr Brigitte Röder (University of Hamburg).

“We demonstrated that healthy persons systematically misattribute touch on the hands to the feet, and vice versa,” Heed adds.

The Start of Things

Neighbouring neurons in the brain react to homologous areas of the skin.

“Previously, scientists believed that a topographical map in the brain was responsible for our conscious experience of where a touch happened.

Parts of the body, such as the hands, feet, and face, are represented on this map based on this concept.

Our current findings, on the other hand, show that additional aspects of touch are also employed to ascribe a touch to bodily parts “Heed agrees.

He refers to the alleged “map” as an anatomical reference system.

Previously, it was thought that spatial perception influenced touch processing, which Heed defines as “where a touch occurs in spatial terms, such as to the left, in front of, or below.”

Many prior discoveries suggested that the brain was very likely employing this other map, sometimes known as an external reference system.

“When components of the body are positioned on the opposite side of the body than they normally are, such as when crossing your legs, the two coordinate systems clash.”

The external coordinate system thus places the left leg on the right side of the body, which contradicts what the brain remembers about which side of the body the leg belongs to.

“Our first goal in our study was to sort out the importance of anatomical perception in the brain as well as the impact of spatial perception,” Heed explains.

The Research

Tactile stimulators were attached to each of the study participants’ hands and feet for the studies.

These stimulators may cause a sensation to be felt on the skin.

The researchers then immediately touched the test subjects on two distinct regions of the body, such as the left foot and the left hand, using this impulse generator.

The participants then stated or demonstrated where they felt the first touch.

This method was then performed on each test subject hundreds of times.

The study participants were required to cross their feet or hands at times, while their limbs stayed in their natural positions at other times.

“Remarkably, in 8% of all cases, the first touch was assigned to a section of the body that had not even been touched — this is a type of phantom experience,” Stephanie Badde adds.

The Reasons for This

The prior belief that the attributed location of touch on the body is determined by “maps” of the body is no longer valid.

Tobias Heed explains, “We show that phantom feelings are dependent on three criteria.”

“The most crucial factor is the limb’s identity, whether it’s a hand or a foot.”

This is why a touch, on one hand, is frequently misinterpreted as a touch on the other.”

The side of the body where the contacted limb belongs is the second most critical element, which explains why a touch on the left foot might occasionally be misinterpreted as a touch on the left hand.

Another factor is the canonical anatomical position of the bodily component in question, such as where the hands or feet are typically situated in space.

The researchers demonstrated this in their experiment with crossed body parts, in which the left hand was placed on the right side.

If the left hand is touched, the brain may misinterpret this as a touch on the right foot — a portion of the body that does not belong to the same side of the body or to the same external spatial position as the part of the body that was actually touched.

The typical location of the body component that was touched is decisive: “The left hand causes a response from a region of the body that is now positioned where the touched hand would typically be,” Stephanie Badde explains.

The results of this research provide new light on how the brain represents our own bodies.

“The findings could, for example, be used to spur further study into the origins of phantom pain,” says Tobias Heed.

“Touch-based artificial system development is now predicated on the firm assumption that the problem of touch can be solved by employing one or several maps.

However, alternate processing methods may be more efficient for some types of activity.”

This discovery could also lead to work identifying how somatosensory information is encoded, which could be utilised to incorporate sensory data into brain-machine interfaces. This could make it possible for robotic limbs and prostheses to feel and respond to tactile input.

Who knows, perhaps new research and thinking in this area will one day enable my table tennis pal Dhruv to detect through his artificial limb that he can also experience sensations in his arm.

That day, I am certain it will stimulate goosebumps in me.

-End-

For other interesting blog, you may click below:

Is there magic pill to get incredible life to heal depression?

How Karim Ali, Unsung Hero Of Assam makes spectacular fame to Dance

How band BTS thrilled young generation to imagine a better world in UN?